- Submit Nominations for Partnership for Quality Measurement (PQM) Committees

- Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation of the Medicare Program (Executive Order 14192) - Request for Information

- Dr. Mehmet Oz Shares Vision for CMS

- CMS Refocuses on its Core Mission and Preserving the State-Federal Medicaid Partnership

- Social Factors Help Explain Worse Cardiovascular Health among Adults in Rural Vs. Urban Communities

- Reducing Barriers to Participation in Population-Based Total Cost of Care (PB-TCOC) Models and Supporting Primary and Specialty Care Transformation: Request for Input

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- 2025 Marketplace Integrity and Affordability Proposed Rule

- Rural America Faces Growing Shortage of Eye Surgeons

- NRHA Continues Partnership to Advance Rural Oral Health

- Comments Requested on Mobile Crisis Team Services: An Implementation Toolkit Draft

- Q&A: What Are the Challenges and Opportunities of Small-Town Philanthropy?

- HRSA Administrator Carole Johnson, Joined by Co-Chair of the Congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus Congresswoman Lauren Underwood, Announces New Funding, Policy Action, and Report to Mark Landmark Year of HRSA's Enhancing Maternal Health Initiative

- Biden-Harris Administration Announces $60 Million Investment for Adding Early Morning, Night, and Weekend Hours at Community Health Centers

With Rural Health Care Stretched Thin, More Patients Turn To Telehealth

July 7, 2019, National Public Radio’s Life and Health in Rural America’s Series

After a difficult time in her life, Jill Hill knew she needed therapy. But it was hard to get the help she needed in the rural town she lives in, Grass Valley, Calif., until she found a local telehealth program.

Telehealth turned Jill Hill’s life around.

The 63-year-old lives on the edge of rural Grass Valley, an old mining town in the Sierra Nevada foothills of northern California. She was devastated after her husband Dennis passed away in the fall of 2014 after a long series of medical and financial setbacks.

“I was grief-stricken and my self-esteem was down,” Hill remembers. “I didn’t care about myself. I didn’t brush my hair. I was isolated. I just kind of locked myself in the bedroom.”

Hill says knew she needed therapy to deal with her deepening depression. But the main health center in her rural town had just two therapists. Hill was told she’d only be able to see a therapist once a month.

Then, Brandy Hartsgrove called to say Hill was eligible via MediCal (California’s version of Medicaid) for a program that could offer her 30-minute video counseling sessions twice a week. The sessions would be via a computer screen with a therapist who was hundreds of miles south, in San Diego.

Hartsgrove co-ordinates telehealth for the Chapa-de Indian Health Clinic, which is a 10-minute drive from Hills’s home. Hill would sit in a comfy chair facing a screen in a small private room, Hartsgrove explained, to see and talk with her counselor in an otherwise traditional therapy session.

Hill thought it sounded “a bit impersonal;” but was desperate for the counseling. She agreed to give it a try.

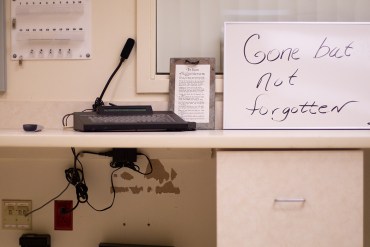

Coordinator Brandy Hartsgrove demonstrates how the telehealth connection works at The Chapa-de Indian Health Clinic in Grass Valley, Calif. Via this video screen, patients can consult doctors hundreds of miles away.

Hill is one of a growing number of Americans turning to telehealth appointments with medical providers in the wake of widespread hospital closings in remote communities, and a shortage of local primary care doctors, specialists and other providers.

Long-distance doctor-to-doctor consultations via video also fall under the “telehealth” or “telemedicine” rubric.

A recent NPR poll of rural Americans found that nearly a quarter have used some kind of telehealth service within the past few years; 14% say they received a diagnosis or treatment from a doctor or other health care professional using email, text messaging, live text chat, a mobile app, or a live video like FaceTime or Skype. And 15% say they have received a diagnosis or treatment from a doctor or other health professional over the phone.

Click here to access the entire article.

How the Federal Government Supports State and Local Efforts to Improve Rural Health: A Q&A with Tom Morris

Tom Morris, M.P.A., is associate administrator of rural health policy for the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). With a budget of $317 million, his office oversees a wide range of activities—from conducting research and policy analysis to providing technical assistance to hospitals in danger of closing. His office also recently assumed responsibility for administering a new program that targets the federal response to the opioid crisis to the particular needs of rural communities.

Morris took part in regional meetings of the Reforming States Group, the Milbank Memorial Fund’s bipartisan network of state executive and legislative leaders. As described in our issue brief, Supporting Rural Health: Options for State Policymakers, the meetings focused on rural health concerns and spotlighted actionable solutions.

The Milbank Memorial Fund asked Morris how HRSA and other federal agencies are working to support these approaches, including health care delivery models that promote population health, rural health workforce development, and research and policy focused on rural communities.

As a group, rural residents are older and poorer than other Americans and have worse access to health care services, as well as higher mortality rates from potentially preventable conditions. Some parts of rural America have also been ravaged by “deaths of despair” from alcohol, drug overdoses, or suicide. How is the Office of Rural Health Policy working to address these multifaceted issues?

Part of what we do is to quantify these problems so we can make sure rural issues are front and center when policy issues are considered. The opioid crisis is a good example. A lot of the initial research, both at HHS and nationally, tended to focus on opioid overdose rates at the state level. We weren’t seeing a lot about what happens in rural communities. We try to fill those gaps with research and by gathering perspectives from rural communities. Click here to read the full interview!

Rural Hospitals Support Wage Index Reform

Hospital and health system executives and practitioners were largely supportive of the CMS’ proposed changes to the wage index that they say has disproportionately impacted rural providers.

Hospital presidents and concerned employees, predominantly from rural areas, claim in some of more than 2,000 public comments that the “fundamentally flawed” system the CMS uses to set hospital payments has led to hospital closures. They hope that the agency’s plan in October to raise the index for low-wage hospitals at the expense of decreasing it for high-wage hospitals will close a wide payment disparity. Click here to access the July 3, 2019 article from Modern Healthcare.

ARC Issues County Economic Status Designations for FY 2020

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) has released its County Economic Status Designations for Fiscal Year 2020, which annually ranks the economic status of each of the Region’s 420 counties using national data. According to the rankings, 80 Appalachian counties — the lowest number in over a decade — will be considered Distressed (ranking among the worst 10% of counties in the nation). Meanwhile, 110 counties will be considered At-Risk (ranking between the worst 10–25% of counties in the nation); 217 counties will be considered Transitional (ranking between worst 25% and best 25% of counties in the nation); 10 counties will be considered Competitive (ranking between best 25% and best 10% of counties in the nation); and 3 counties will be considered Attainment (ranking among the best 10% of counties in the nation). The report also shows that 29 Appalachian counties across 8 states experienced positive shifts in the economic status since FY 2019. This primarily includes counties in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi which each have five or more counties experiencing positive economic status shift. At the same time, 18 Appalachian counties will experience negative shifts in their economic status since FY 2019. This primarily includes coal impacted counties in Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania.

To determine the economic status of each of the Region’s 420 counties, ARC applies a composite index formula drawing on the latest data available on per capita market income combined with the previous three-year average unemployment rate, and the previous five-year poverty rates. With this data, each county is classified into one of the five economic designations. An analysis of the data also found that poverty rates in Appalachia and the nation as a whole dropped 0.4 percentage points and 0.5 percentage points respectively. This finding shows a widening gap between Appalachia’s poverty rate (16.3 percent) and the nation’s rate (14.6 percent).

The County Economic Status Designations help determine match requirements for ARC grants.

Have Cancer, Must Travel: Patients Left In Lurch After Hospital Closes

This is the first installment in Kaiser Health News’ year-long series, No Mercy, which follows how the closure of one beloved rural hospital disrupts a community’s health care, economy and equilibrium.

FORT SCOTT, Kan. — One Monday in February, 65-year-old Karen Endicott-Coyan gripped the wheel of her black 2014 Ford Taurus with both hands as she made the hour-long drive from her farm near Fort Scott to Chanute. With a rare form of multiple myeloma, she requires weekly chemotherapy injections to keep the cancer at bay.

Continuity of care is crucial for cancer patients in the midst of treatment, which often requires frequent repeated outpatient visits. So when Mercy Hospital Fort Scott, the rural hospital in Endicott-Coyan’s hometown, was slated to close its doors at the end of 2018, hospital officials had arranged for its cancer clinic — called the “Unit of Hope” — to remain open.

The full article can be accessed here.

Updates to PA Free Quitline

The Pennsylvania Department of Health’s Division of Tobacco Prevention and Control, in consultation with the National Jewish Health and Public Health Management Corporation, is implementing changes in cessation products by the PA Free Quitline. As of July 1, 2019, a 3-month supply of Chantix will be offered to newly enrolled Quitline participants on Medicaid.

HRSA Releases Updated HPSA Lists

The Health Resources and Services Administration announced the release of an updated list of geographic areas, population groups, and facilities designated as primary care, mental health, and/or dental care Health Professional Shortage Areas.

Penn State Team Supports Implementation of Novel Pennsylvania Rural Health Model

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was formally announced in January 2017 and officially launched in the state on Jan. 1, 2019. The effort will continue through 2024.

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Pennsylvania is the first state in the nation to design and implement an alternative payment model focused solely on rural hospitals, with an emphasis on both containing health care spending and transforming care to better meet community needs.

A multi-disciplinary team of Penn State faculty and staff members, led by Lisa Davis, outreach associate professor of health policy and administration and director of the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health and Outreach, and Dennis Scanlon, distinguished professor of health policy and administration and director of the Center for Health Care and Policy Research, will work with the Pennsylvania Department of Health to support and evaluate the implementation of the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model.

The Pennsylvania Rural Health Model was formally announced in January 2017 and officially launched in the state on Jan. 1, 2019. The effort will continue through 2024.

The model, developed with funding from the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, addresses the financial challenges that rural hospitals face by transitioning them from fee-for-service to global budget payments.

Currently, five rural hospitals and five health plans are participating in the model’s first implementation year. The Pennsylvania Department of Health and its sub-contractors continue to recruit additional hospitals and plans. Pending the passage of state legislation, the Rural Health Redesign Center (RHRC) will be established as an independent entity to administer the model.

Through a contract with the commonwealth, the Penn State team will engage in a projects and analysis associated with the first phase of the model and the establishment of the RHRC.

Davis will lead the drafting of by-laws, human resources policies, and marketing and communications plans for the RHRC. She also will explore funding opportunities for the RHRC and participating hospitals to extend the reach and impact of the model.

Scanlon will lead an analysis to inform the health needs of rural populations and will chronicle the evolution and history of the model.

Joel Segel, assistant professor of health policy and administration, will provide assistance with data aggregation and analytic support using data from a variety of sources. Segel and his team will assist with aggregation of data related to financial performance, population health, access to care, and quality from model stakeholders, all of which represent important targets for the model.

A computational and spatial analysis team, led by Guangqing Chi, associate professor of rural sociology and demography and public health sciences, will work with a team to understand the geospatial needs of the model and will provide consulting expertise. A data warehouse planning team, led by Max Crowley, assistant professor of human development and family studies and director of Penn State’s Administrative Data Accelerator, will map options and opportunities for the development of a long-term data solution for the RHRC. The solution will be focused on best practices for receiving, storing, managing, securing and using data from stakeholders.

2020 Census: Who’s At Risk of Being Miscounted?

The Urban Institute has published a report identifying the populations at risk for being miscounted in the 2020 U.S. Census. According to the Institute, the decennial census, which aims to count every US resident each decade, is critical to our democracy. It affects congressional seats and funding decisions at every level of government.

But the 2020 Census faces unprecedented challenges and threats to its accuracy. Demographic changes over the past decade will make the population harder to count. And underfunding, undertested process changes, and the last-minute introduction of a citizenship question could result in serious miscounts, potentially diminishing communities’ rightful political voice and share of funding.

To understand how these factors could affect the 2020 Census counts, the Urban Institute created projections under three scenarios—reflecting the miscount risk as low, medium, or high. Access the report at https://apps.urban.org/features/2020-census/?elq_cid=2420582&x_id=.

Community HealthChoices (CHC) in Pennsylvania is Coming in January 2020

The counties included in the third and final phase of the program’s implementation are:

- Lehigh/Capital Zone: Adams, Berks, Cumberland, Dauphin, Fulton, Franklin, Huntingdon, Lancaster, Lebanon, Lehigh, Northampton, Perry, York.

- Northeast Zone: Bradford, Carbon, Centre, Clinton, Columbia, Juniata, Lackawanna, Luzerne, Lycoming, Mifflin, Monroe, Montour, Northumberland, Pike, Schuykill, Snyder, Sullivan, Susquehanna, Tioga, Union, Wayne, Wyoming.

- Northwest Zone: Cameron, Clarion, Clearfield, Crawford, Elk, Erie, Forest, Jefferson, McKean, Mercer, Potter, Venango, Warren.

What you need to know:

- CHC information for providers or participants can be found at healthchoices.pa.gov. The website will be updated as events are scheduled, so please check back often.

- Click here to take our online trainings and read CHC fact sheets.

- Access a list of frequently asked questions (FAQs) about CHC by clicking here.

- Contact a CHC managed care organization (CHC-MCO) to become part of their provider network:

- AmeriHealth Caritas

- Phone: 1-800-521-6007 // Email: chcproviders@amerihealthcaritas.com

- Pennsylvania Health & Wellness

- Phone: 1-844-626-6813 // Email: information@pahealthwellness.com

- UPMC Community HealthChoices

- Phone: 1-844-860-9303 // Email: CHCProviders@UPMC.edu

- Sign up and encourage your peers to subscribe to CHC emails here. By signing up, you will receive regular communications regarding CHC distributed from the Office of Long-Term Living.

- AmeriHealth Caritas

Here’s a schedule of what’s coming in 2019

July 2019-October 2019

- An introductory flyer will be sent to participants identified within the CHC population. View the flyer by clicking here.

- Notices and enrollment packets will be mailed to participants.

- Information on the LIFE program will be sent to potentially eligible participants.

- Informational sessions will be held for participants to learn about CHC and how to select a CHC-MCO.

- For a full look at the CHC implementation timeline, click here.

- To learn the difference between CHC and HealthChoices, click here.

If you have any questions, please contact the Office of Long-Term Living’s Provider Hotline at 1-800-932-0939

A listserv has been established for ongoing updates on the CHC program. It is titled OLTL-COMMUNITY-HEALTHCHOICES, please visit the ListServ Archives page at http://listserv.dpw.state.pa.us to update or register your email address.

Please share this email with other members of your organization as appropriate. Also, it is imperative that you notify the Office of Long-Term Living for changes that would affect your provider file, such as addresses and telephone numbers. Mail to/pay to addresses, email addresses, and phone numbers may be updated electronically through ePEAP, which can be accessed through the PROMISe™ provider portal. For any other provider file changes please notify the Bureau of Quality and Provider Management Enrollment and Certification Section at 1-800-932-0939 Option #1.

To ensure you receive email communications distributed from the Office of Long-Term Living, please visit the ListServ Archives page at http://listserv.dpw.state.pa.us to update or register your email address.