- Telehealth Study Recruiting Veterans Now

- USDA Delivers Immediate Relief to Farmers, Ranchers and Rural Communities Impacted by Recent Disasters

- Submit Nominations for Partnership for Quality Measurement (PQM) Committees

- Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation of the Medicare Program (Executive Order 14192) - Request for Information

- Dr. Mehmet Oz Shares Vision for CMS

- CMS Refocuses on its Core Mission and Preserving the State-Federal Medicaid Partnership

- Social Factors Help Explain Worse Cardiovascular Health among Adults in Rural Vs. Urban Communities

- Reducing Barriers to Participation in Population-Based Total Cost of Care (PB-TCOC) Models and Supporting Primary and Specialty Care Transformation: Request for Input

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- 2025 Marketplace Integrity and Affordability Proposed Rule

- Rural America Faces Growing Shortage of Eye Surgeons

- NRHA Continues Partnership to Advance Rural Oral Health

- Comments Requested on Mobile Crisis Team Services: An Implementation Toolkit Draft

- Q&A: What Are the Challenges and Opportunities of Small-Town Philanthropy?

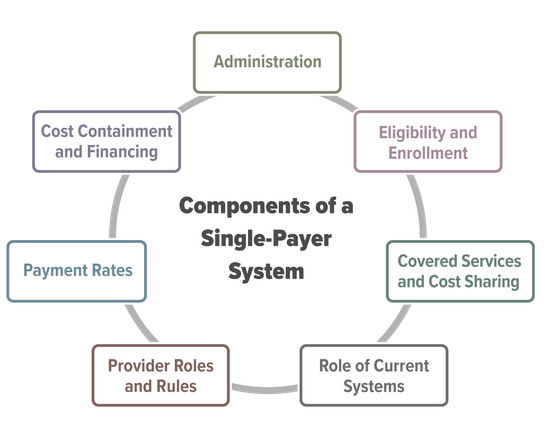

Congressional Budget Office Releases Report on Single-Payer Health Care System

Key Design Components and Considerations for Establishing a Single-Payer Health Care System

Congressional interest in substantially increasing the number of people who have health insurance has grown in recent years. Some Members of Congress have proposed establishing a single-payer health care system to achieve universal health insurance coverage. In this report, CBO describes the primary features of single-payer systems, as well as some of the key considerations for designing such a system in the United Stat es.

es.

Establishing a single-payer system would be a major undertaking that would involve substantial changes in the sources and extent of coverage, provider payment rates, and financing methods of health care in the United States. This report does not address all of the issues that the complex task of designing, implementing, and transitioning to a single-payer system would entail, nor does it analyze the budgetary effects of any specific bill or proposal.

Primary Care Clinician Participation in the CMS Quality Payment Program

Clinton MacKinney, MD, MS; Fred Ullrich, BA; and Keith J. Mueller, PhD

Approximately 10 percent of primary care clinicians participate in Advanced Alternative Payment Models (A-APMs) and less than 30 percent of primary care clinicians participate in the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System. Metropolitan primary care clinicians are more likely to participate in A-APMs than non-metropolitan primary care clinicians.

Click to download a copy: Primary Care Clinician Participation in the CMS Quality Payment Program

Open Comment Period for Pennsylvania WIC

The Pennsylvania Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program is accepting public comments on its program. Please consider mentioning the importance of oral health in WIC programming. Comments can be provided at upcoming WIC Public Meetings. Written comments can be sent via email to bmellott@pa.gov or mailed to The Department of Health, Bureau of Women, Children, Infants and Children (WIC), 625 Forster St., 7 West, Health and Welfare Building, Harrisburg, PA 17120. Written comments should be received by May 31.

Can we heal rural health? All eyes are on Pennsylvania’s bold experiment | Opinion

By Rachel Levine and Andy Carter, For the Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 2019

Rural communities and their hospitals are struggling.

In terms of health and well-being, rural Pennsylvania and urban Philadelphia have all too much in common, including high rates of child poverty and mortality, food insecurity, and chronic disease.

In terms of the health care needed to address these issues, rural hospitals face some unique challenges. These include sustaining a wide array of services for smaller numbers of patients due to sparsely populated geographies. About half of Pennsylvania’s rural hospitals operate at a loss and are at risk for closure.

Respected research organizations have reported on this problem nationwide. Since 2010, 104 U.S. rural hospitals have closed, two of them in Pennsylvania.

Pennsylvania’s bold experiment

In partnership with the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, the Pennsylvania Department of Health’s new Rural Health Model flips the script on hospital care. In place of hospitals’ traditional focus — treating patients when they are sick or injured — the new model also aims to reward hospitals for keeping patients healthy and out of the hospital altogether.

To accomplish these goals, the model changes the way hospitals are paid.

Typically, hospitals receive payment for each health care service they provide. With the Rural Health Model, hospitals get paid based on annual budgets, which provides more consistent cash flow. These budgets define the financial resources hospitals will have during the year — independent of how many patients are hospitalized or come to emergency rooms. Insurers (commercial and Medicare) and hospitals work together to establish budgets based on the payments hospitals typically received in the past.

With their financial footings a bit more predictable, hospitals can redirect resources and invest in services and partnerships to improve community health. Hospitals are encouraged to focus on keeping people healthy.

This new payment approach not only provides a measure of stability for hospitals, but also for rural communities and jobs.

In metropolitan areas, with a pick of health care systems and services, it may be hard to imagine how important a hospital is to its rural community. In emergencies, that hospital may be the only source of care for 20 miles or more.

Hospitalizations in rural Pennsylvania, across the state, and nationwide are going down.

Hospitals and health systems are shifting care to outpatient and home settings whenever safe and appropriate. Doctors, nurses, and health educators are working with patients, encouraging them to seek preventive care and improve health habits. The goal is to foster better quality of life and avoid intensive and costly inpatient care.

The Rural Health Model gives hospitals predictable finances — those annual budgets — and, potentially, additional flexibility with which to foster this move to better health and lower health care spending.

Now, instead of focusing on expanding services just for the sake of growing market share under the traditional fee-for-service model, hospitals can focus on providing the services most needed by the community. This right-sizing frees up resources to focus on the services needed to address the community’s biggest health challenges (diabetes, for example) and to kick start the virtuous cycle of better health and less need for hospital care.

Five Pennsylvania hospitals have signed up to test out this new payment strategy. (Five insurers have also joined the pilot.) The hospitals have defined strategies for how they will move from just providing sick care to also helping improve the overall health of their communities. Common strategies include better care coordination for patients with chronic disease and better geriatric care for older adults, with the goal of reducing expensive emergency room visits.

The pressing need to help rural communities become healthier, and the potential for this model, has attracted interest from scores of state and federal government agencies and health policy organizations. They really want to make this model work, and effective collaboration is key.

Creating the Rural Health Redesign Center would establish the hub to bring these resources together, to help with the planning and analysis needed to identify successful strategies and replicate them. Five hospitals are using the model now, and we have high interest from up to 25 additional hospitals in joining them over the next two years. Learning from one another about what works and what doesn’t will speed progress.

State legislation is needed to set up the Rural Health Redesign Center. Senate Bill 314, sponsored by Senator Lisa Baker, and House Bill 248, sponsored by Representative Tina Pickett, both have bipartisan support.

Governments, health departments, and hospitals across the nation are watching Pennsylvania’s experiment carefully. Since starting work on this model several years ago, we’ve heard from over a dozen different states, all asking: “Is it working?”

We invite you to pay close attention as well, and to learn more about how five hospitals and insurers are working together, exploring a new and better way to care for their communities. Pennsylvania’s Rural Health Model could help to usher in a new era of health care.

Rachel Levine, MD is Pennsylvania Secretary of Health. Andy Carter is president and CEO of the Hospital and Healthsystem Association of Pennsylvania.

Final Rule Announced Health Insurance Benefit and Payment Parameters

Last week, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the final Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for the 2020 benefit year, a document that sets forth instructions to insurers participating in the Health Insurance Exchanges or “Marketplaces”. Among the changes for 2020 are flexibilities related to the duties and training requirements for the Navigator program and opportunities for innovations in the direct enrollment process. In 2018 and 2019, the percentage of enrollments in the federal exchange (healthcare.gov) by rural residents remained unchanged at 18 percent.

HHS and CMS Announce New Value-Based Care Initiatives

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have announced the CMS Primary Cares Initiative. Administered through the CMS Innovation Center, the new initiative will provide primary care practices and other providers with five new payment model options under two paths: Primary Care First (PCF) and Direct Contracting (DC). Both models provide incentives to reduce hospital utilization and total cost of care by adjusting payments to providers’ performance. While the PCF models focus on individual primary care practice sites, the three DC payment model options aim to engage a wider variety of organizations that have experience taking on financial risk and serving larger patient populations. Last year, the RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis and Stratis Health published a policy brief on the priorities of rural health leaders about value-based payment models.

Differences in Care Processes Between Community-Entry Versus Post-acute Home Health for Rural Medicare Beneficiaries

Medicare beneficiaries may be admitted to home health following an inpatient stay (post-acute) or directly from the community (community-entry). An analysis of Medicare data for rural, fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries who utilized home health from 2011 to 2013 found significant differences in care processes between community-entry and post-acute home health. Compared to post-acute home health episodes, community-entry home health episodes on average were longer; less likely to include physical, occupational, and speech therapy visits; more likely to include medical social work visits; and less likely to be initiated on the physician-ordered start date or within two days of referral. Results suggest community-entry and post-acute home health are serving different needs for rural Medicare beneficiaries, which provides preliminary support for distinguishing between the two types of episodes in payment policy reform.

ONC Brief on Electronic Capabilities of Hospitals

The Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) reports that nearly all hospitals provided patients with the ability to electronically view and download their personal information in 2017. However, Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and small rural hospitals were less likely than larger and urban hospitals to be able to transmit that data and to have view, download, and transmit (VDT) capabilities. Under the Promoting Interoperability Program (PI), hospitals are required to use electronic health records technology. Another aspect of the program is to promote patients’ ability to view and download their personal health information. The cost of electronic health record systems and limited access to broadband are two of the barriers to electronic capabilities in rural health care settings. See the Policy Updates section below for requests for comment on recent proposals on electronic health information networks.

ARC on the State of Health Disparities in Appalachia

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a federal agency created by Congress to partner with state and local governments and promote economic development for the region. This month, the ARC released three separate issue briefs on health disparities in the 13 states of the region – Alabama, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. The briefs describe the factors unique to the region that contribute to disparities related to obesity, opioid misuse, and smoking, and provide recommendations and practical strategies for communities.

Nonmetro Counties Gain Population for Second Straight Year

From the Daily Yonder…

Rural America’s population grew by 0.1 percent from 20017 to 2018. The growth was small and clustered near metropolitan areas. But it reverses the trend of population loss that occurred from 2011 to 2016.

The size of the non-metropolitan population crept up for the second year in a row in 2018, adding about 37,000 residents to reach 46.1 million.

That’s a gain of about 0.1 percent, according to a report from demographer Kenneth M. Johnson at the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy. The rate of growth is roughly the same as the growth rate from 2016 to 2017, when non-metropolitan counties added 33,000 residents.

The overall U.S. population grew by about 0.6 percent over the last year.

While the gains for non-metropolitan America were scant, they continue to reverse the historic drop in non-metropolitan population that occurred from 2011-16.

The map shows which counties gained or lost population from 2017 to 2018. County-level data is available a map. Or see the map in a new, full-sized window.

About half of America’s 2,000 or so non-metropolitan counties gained population, while about three quarters of metropolitan counties did.

Rural America’s net growth came from rural counties that are adjacent to metropolitan areas, Johnson said in his report. Those counties gained 46,000 residents, while non-metro counties that don’t touch a metro area lost 9,000 residents.

Johnson said non-metro counties grew from a combination of migration (more people moving into a county than leaving it) and natural increase (more births than deaths). The rate of natural increase is dwindling, Johnson said.

Growth rates in non-metropolitan American varied by region. “The fastest growing counties have recreational and scenic amenities that attract migrants including retirees from elsewhere in the United States,” according to the report. In contrast, farm counties had more people leave than move into the counties.

The Census Bureau, which released the 2018 population estimates Wednesday (April 18, 2019), noted that the South and West tended to have the fastest numerical growth in counties.

How this story defines rural: This story uses the Office of Management and Budget metropolitan statistical area system to define rural. Rural counties are defined as those that are not in a metropolitan statistical area or MSA. In this story, rural is synonymous with non-metropolitan. There are numerous ways to define rural. You can learn more (much more!) from the USDA Economic Research Research and the U.S. Census.