- Submit Nominations for Partnership for Quality Measurement (PQM) Committees

- Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation of the Medicare Program (Executive Order 14192) - Request for Information

- Dr. Mehmet Oz Shares Vision for CMS

- CMS Refocuses on its Core Mission and Preserving the State-Federal Medicaid Partnership

- Social Factors Help Explain Worse Cardiovascular Health among Adults in Rural Vs. Urban Communities

- Reducing Barriers to Participation in Population-Based Total Cost of Care (PB-TCOC) Models and Supporting Primary and Specialty Care Transformation: Request for Input

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- Secretary Kennedy Renews Public Health Emergency Declaration to Address National Opioid Crisis

- 2025 Marketplace Integrity and Affordability Proposed Rule

- Rural America Faces Growing Shortage of Eye Surgeons

- NRHA Continues Partnership to Advance Rural Oral Health

- Comments Requested on Mobile Crisis Team Services: An Implementation Toolkit Draft

- Q&A: What Are the Challenges and Opportunities of Small-Town Philanthropy?

- HRSA Administrator Carole Johnson, Joined by Co-Chair of the Congressional Black Maternal Health Caucus Congresswoman Lauren Underwood, Announces New Funding, Policy Action, and Report to Mark Landmark Year of HRSA's Enhancing Maternal Health Initiative

- Biden-Harris Administration Announces $60 Million Investment for Adding Early Morning, Night, and Weekend Hours at Community Health Centers

Understanding Encampments of People Experiencing Homelessness and Community Responses

The National Alliance to End Homelessness has released a new report, Understanding Encampments of People Experiencing Homelessness and Community Responses: Emerging Evidence as of Late 2018, to discuss different models to assist people living in encampments by removing barriers to accessing services and housing through the use of navigation centers, such as those used in San Francisco. Evidence shows that clearing out encampments without follow-up support services does nothing to solve the actual problem but instead creates unnecessary trauma for inhabitants. More research on the demographic characteristics of people living in encampments would better inform policy and program initiatives.

Impending “Public Charge” Rule Could Drive Up the Uninsured Rate for Children

From the Pennsylvania Partnerships for Children

The “public charge” test refers to the evaluation by federal immigration officials to determine whether a person applying for a visa or green card is likely to rely on government benefits. The final rule, which was published last week by the Department of Homeland Security, changes the public charge definition by adding more programs into the determination, including Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

It is important to note what is not included in the final rule. Children, pregnant women and new mothers 60-days post-partum on Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) are not factored into the public charge determination.

However, confusion and fear among families with mixed immigration status may drive individuals to withdraw their eligible citizen children from essential programs providing health care, food and housing. This is what is known as the “chilling effect,” and according to the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Immigrant Child and Family Health and many other child health experts and advocates, we are already seeing this occur since the rule was proposed last fall, which underscores the concern of this rule driving up the child uninsured rates across the country.

The final rule is scheduled to go into effect October 15, 2019 unless Congress or the courts act to block implementation of the regulation.

Education about this rule change is key – we must ensure that children continue to enroll and receive the preventive health care and nutritional assistance necessary for their healthy development.

For more information about public charge, please refer to this list of resources.

Rural Pennsylvanians Have Nearby Access to Opioid Treatment, but Still Travel Far to Receive it

Rural Pennsylvania Medicaid enrollees diagnosed with opioid use disorder are driving an average of four times as far as their nearest prescriber to receive medication-assisted treatment, according to an analysis led by University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health researchers.

The study, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, also found that the farther people have to travel, the less likely they are to adhere to medication-assisted treatment, which is the standard of care for opioid use disorder.

“While people in rural areas with opioid use disorder face challenges obtaining medication-assisted treatment, another important finding from our research is that these same people have substantial contact with their primary care physician, averaging four visits per year,” said lead author Dr. Evan Cole, research assistant professor in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Health Policy and Management. “By providing training and support to primary care physicians to provide medication-assisted treatment to their patients, policymakers might stimulate increases in treatment access in local communities.”

“While people in rural areas with opioid use disorder face challenges obtaining medication-assisted treatment, another important finding from our research is that these same people have substantial contact with their primary care physician, averaging four visits per year,” said lead author Dr. Evan Cole, research assistant professor in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Health Policy and Management. “By providing training and support to primary care physicians to provide medication-assisted treatment to their patients, policymakers might stimulate increases in treatment access in local communities.”

Medication-assisted treatment is the use of medications, such as buprenorphine, naltrexone or methadone, often with counseling, to treat opioid use disorder. The medications relieve opioid cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Providers must complete training and be approved to prescribe buprenorphine, and methadone can be dispensed only by licensed clinics for opioid use disorder.

Through a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality to the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services, Cole and his colleagues reviewed Pennsylvania Medicaid claims data from 2014 to 2015 for 7,930 enrollees with a diagnosis of opioid use disorder living in 23 rural Pennsylvania counties heavily impacted by the opioid crisis. Pennsylvania is the seventh–largest Medicaid program by enrollment, the fourth–largest by expenditure and has the third–largest rural population, compared to other states.

The team mapped availability of providers of medication-assisted treatment and the actual location of where each enrollee was receiving treatment. The average distance to the nearest possible provider of medication-assisted treatment was 4.2 miles among rural enrollees with opioid use disorder. When the researchers limited it to only physicians with a high likelihood of taking new Medicaid recipients, the average distance was 12.6 miles. However, despite closer options, the Medicaid enrollees in the study were traveling an average of 48.8 miles for treatment.

“We can’t say for sure why the enrollees were traveling so much farther than necessary for treatment. We couldn’t measure things like wait times for appointments or patient preferences for particular providers,” Cole said. “But we do know that only 20 percent of those with opioid use disorder were diagnosed by their primary care physician. More frequently, they were diagnosed by a behavioral health provider, who then likely referred them to treatment.”

Getting someone with opioid use disorder into treatment is only the beginning, Cole said. His team took their analysis further and found that enrollees who travelled more than 45 miles to treatment had 29% lower odds of remaining adherent to medication-assisted treatment. There is strong evidence that adherence to medication-assisted treatment is related to a lower risk of relapse and improved outcomes.

“Primary care physicians don’t get a lot of training in addiction, so they may be reluctant to treat it due to concerns about administrative burdens on their practice or stigma about taking on new patients with opioid addiction,” Cole said. “But what we found is that the people in rural communities with opioid use disorder are already being seen by these primary care physicians for other reasons. If we can equip these physicians with training and administrative and clinical support to offer such treatment, and show them that they’ll be treating the patients they already have, they could be in the right place at the right time to address important gaps in access to addiction treatment.”

Cole said that future research will need to examine whether patients who are traveling great distances for medication-assisted treatment eventually switch to closer providers, and whether that change is associated with improved outcomes.

The research was funded by Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality grant 1R18HS025072-01. Ellen DiDomenico, M.S., of the Pennsylvania Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs is the principal investigator of the AHRQ grant, and is a co-author of the study.

Newly Released! Community HealthChoices (CHC) Toolkit

Through an Innovation Lab grant from the HealthSpark Foundation, the Pennsylvania Assistive Technology Foundation (PATF) collaborated with the Pennsylvania Health Law Project (PHLP) to create and disseminate a toolkit of materials that will help Pennsylvanians better understand Community HealthChoices (CHC). The toolkit, includes:

- CHC Infographic (English and Spanish)

- Person-Centered Service Planning

- How to Appeal a Denial in Community HealthChoices

- Where to Call for Help with Problems Consumers Experience in CHC – Southeast PA and Southwest PA

- Funding Your Assistive Technology: A Guide to Funding Resources in Pennsylvania (English and Spanish)

What is Community HealthChoices (CHC)?

CHC is a new waiver program for individuals over 21 years old with a disability who previously received services through the Independence, CommCare, or Aging Waivers. These individuals select or are automatically enrolled in one of three managed care organizations that have contracts with the state. Services are obtained through service providers who have contracts with these managed care organizations.

Services provided through CHC include all the Home and Community-Based Services formerly provided by waivers, plus a few new ones, for older adults and adults with physical disabilities or traumatic brain injury.

This program is in effect in 14 counties in Southwest Pennsylvania and 5 counties in Southeast Pennsylvania as of January 2019. The rest of the state will be covered in January 2020.

Pennsylvania Rural Hospital Leader Receives National Quality Spirit Award

University Park, Pa. (August 21, 2019) – Lannette Fetzer, quality improvement coordinator at the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health (PORH), received the Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project (MBQIP) Spirit Award on July 11, 2019 at a national meeting in Bethesda, Maryland, convened by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP).

In 2011, FORHP, created MBQIP to promote high quality care at rural hospitals with 25 beds or fewer that have been designated at the federal level as Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs). Low-volume hospitals participating in the project voluntarily report on a set of quality measures relevant to the care they provide, share data and implement quality improvement initiatives. Currently, 98 percent of the 1,346 CAHs in the United States are reporting rural-relevant quality measures.

The nomination, submitted by Jennifer Edwards, rural health systems manager and deputy director at PORH, recognized Fetzer for being a rural health care leader and advocate since 1995 and for utilizing her extensive clinical experience to provide technical assistance in Pennsylvania and across the nation.

Edwards noted that Fetzer has worked diligently to ensure that the CAHs in Pennsylvania have the support they need to increase their quality metrics and expand quality improvement initiatives. Her efforts have yielded tremendous success as evident by Pennsylvania’s CAHs reporting rate of 100 percent for inpatient and outpatient MBQIP reporting measures. Since Fetzer joined PORH in 2016, Pennsylvania’s national ranking in the annual national recognition of state MBQIP programs has increased from fifth in 2017, to third in 2018 and now first in the nation for 2019.

“Lannette is passionate about rural health care,” said Edwards. “She has successfully partnered with the CAH quality improvement directors to improve patient outcomes across the Commonwealth. We are extremely proud of all her achievements.”

“This is an incredible honor for Lannette” noted Lisa Davis, director of PORH and outreach associate professor of health policy and administration at Penn State. “She is quickly emerging as a leader in the state and nationally for quality reporting and improvement in rural hospitals and health systems. Our office is proud to have Lannette as a member of our staff.”

Pennsylvania has 15 CAHs which serve the most rural communities in the state. Pennsylvania was one of the very first state to achieve 100 percent reporting by CAHs to MBQIP and is one of the few programs in the nation to have a staff member dedicated to quality improvement.

PORH formed in 1991 as a joint partnership between the federal government, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and Penn State. The office is one of 50 state offices of rural health in the nation funded under a program administered by FORHP in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and is charged with being a source of coordination, technical assistance, and networking; and partnership development.

PORH provides expertise in the areas of rural health, agricultural health and safety, and community and economic development. PORH is administratively housed in the Department of Health Policy and Administration in the College of Health and Human Development at Penn State University Park.

Pennsylvania’s Critical Access Hospital Program Ranked Number One in the Nation for Quality Improvement

University Park, Pa. (August 22, 2019) – On July 11, at a national meeting in Bethesda, Maryland, the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) presented ten state offices of rural health with the 2019 Medicare Beneficiary Quality Improvement Project (MBQIP) Quality Performance Awards. These awards recognize achieving the highest reporting rates and levels of improvement in Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) over the past year. CAHs are designated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in recognition of the essential services they provide to rural communities.

This year’s 10 top-performing states are Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Michigan, Utah, Alabama, Nebraska, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota and Wisconsin. These states’ offices of rural health built on their previous successes by investing funding from FORHP into quality-improvement projects and developing technical assistance resources that improve high-quality care in their communities. States also work collaboratively with each Critical Access Hospital and their respective partners to share best practices and utilize data to drive quality improvement in their hospitals.

Pennsylvania recently was ranked as the number one MBQIP program in the nation. The state has 15 CAHs which serve the most rural communities. Pennsylvania was one of the first states to achieve 100 percent reporting by CAHs to MBQIP and is one of the few programs in the nation to have a staff member dedicated to quality improvement.

The federally-funded program that provides technical assistance to the CAHs and supports their quality improvement efforts is administered by the Pennsylvania Office of Rural Health, which is administratively housed in the Department of Health Policy and Administration in the College of Health and Human Development at Penn State University Park.

Formed in 1991, PORH is one of 50 state offices of rural health in the nation funded under a program administered by FORHP. It is charged with being a source of coordination, technical assistance, networking, and partnership development, and provides expertise in the areas of rural health, agricultural health and safety, and community and economic development.

Lannette Johnston, quality improvement coordinator at PORH, said, “This award is evidence of the hard work and dedication that the Pennsylvania CAH quality improvement directors, staff and leadership provide every day to enhance the health of the communities they serve.”

“We are privileged to work with outstanding rural health care leaders who make quality care a top priority in their CAHs,” said Jennifer Edwards, PORH rural health systems manager and deputy director. “Receiving this recognition once again demonstrates their continued commitment to quality improvement.”

HRSA created the quality performance awards to promote high-quality care at rural hospitals with 25 or fewer beds. Hospitals that participate in MBQIP voluntarily report quality measures relevant to the care they provide, share data and take on quality improvement initiatives. Of those engaging in improvement initiatives, 72 percent have improved outcomes on the reported measures.

According to George Sigounas, HRSA administrator, “MBQIP is part of a broader portfolio of activities within HRSA to preserve hospitals and help rural communities to continue their access to quality health care. Ensuring rural hospital viability is an important component of HRSA’s strategic efforts on high-quality and value-based care.”

“We’re happy to work with the states on this effort,” said Tom Morris, FORHP associate administrator. “They’ve done a great job showing that CAHs can be national leaders in quality improvement and that results in better care in rural communities.”

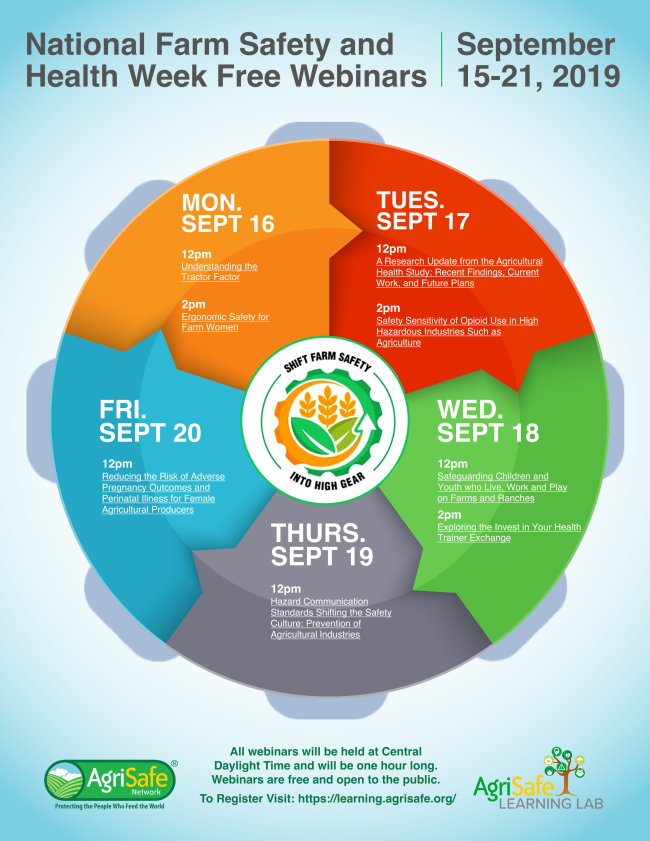

National Farm Safety and Health Week: September 15-21, 2019

AgriSafe Network is excited to be part of National Farm Safety and Health (NFSH) Week 2019. Participate in NFSH Week now by registering for FREE webinars relating to each of the daily topics! All you need to do to register is create a profile on the AgriSafe Learning Lab (which takes less than 2 minutes)! Google Chrome is the recommended web browser for the Learning Lab.

CLICK HERE to register and view a list of presenters!

Burden of Cancer in Pennsylvania Report Available

The Pennsylvania Data Advisory Committee (DAC) is pleased to announce the availability of the 2019 Burden of Cancer in Pennsylvania Report. This report provides a comprehensive analysis of the burden of cancer in Pennsylvania and lists disparities and the harms of cancer for policy makers, program administrators, business and industry leaders, and the citizens of the commonwealth.

Eight cancers were selected for study: cervix uteri, colon and rectum, female breast, leukemia, lung and bronchus, melanoma of the skin, ovary, and prostate. These selections were based on a survey from cancer control partners in Pennsylvania, each cancer’s impact on the overall burden of cancer, and the fact that screenings and preventive measures exist for most of them. This report shows different aspects each cancer including incidence, mortality, comparison by sex, race and ethnicity, US and PA trends, age of diagnosis, stage and 5-year net survival.

The DAC is a committee of the Pennsylvania Cancer Control, Prevention and Research Advisory Board with members representing the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry, the Bureau of Epidemiology, Bureau of Health Statistics and Research and the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control within the Department of Health and selected external organizations.

The report can be accessed on the Pennsylvania Department of Health website at https://www.health.pa.gov/topics/disease/Cancer/Pages/Cancer.aspx

The Candidates and Rural Policy: A Quick Guide

From The Daily Yonder

Here’s a roundup of the candidates’ positions on rural policy and a sampling of their statements about rural.

Eight of 19 Democratic presidential candidates have released comprehensive rural policy plans, and another six have included rural initiatives in other major policy documents, a Daily Yonder review of press reports and candidate websites reveals.

Only one candidate (New York Mayor Bill Deblasio) has been entirely mum on rural, according to our research. The other candidates have at least mentioned rural America on the hustings or in candidate debates. And most have created full rural plans or included rural implications in policy documents on topics such as economic development, healthcare, and conservation.

Candidates with comprehensive rural-policy platforms are former Vice President Joe Biden; South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg; former Ohio U.S. Representative John Delaney; New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand; Colorado Governor John Hickenlooper; Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar; Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders; and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren.

Click here for a table of rural statements and documents from the 19 candidates who qualified for the second round of Democratic primary debates. The candidates are listed in alphabetical order. We’ll update this document as the campaign progresses. If you see errors or omissions, please let us know (tim@dailyyonder.com).

After A Rural Hospital Closes, Delays In Emergency Care Cost Patients Dearly

The loss of the longtime hospital in Fort Scott, Kan., forces trauma patients to deal with changing services and expectations.

Linda Findley’s husband, Robert, died after falling on the ice during a winter storm this February in Fort Scott, Kan. Mercy Hospital had recently closed, and Robert had to be flown to a neurology center 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo., but at least three air ambulance pilots turned down the call from local EMS workers before one accepted.(Christopher Smith for KHN)

FORT SCOTT, Kan. — For more than 30 minutes, Robert Findley lay unconscious in the back of an ambulance next to Mercy Hospital Fort Scott on a frigid February morning with paramedics hand-pumping oxygen into his lungs. A helipad sat just across the icy parking lot from the hospital’s emergency department, which had recently shuttered its doors, like hundreds of rural hospitals nationwide.

Suspecting an intracerebral hemorrhage and knowing the ER was no longer functioning, the paramedics who had arrived at Findley’s home called for air transport before leaving. For definitive treatment, Findley would need to go to a neurology center located 90 miles north in Kansas City, Mo. The ambulance crew stabilized him as they waited.

But the dispatcher for Air Methods, a private air ambulance company, checked with at least four bases before finding a pilot to accept the flight, according to a 911 tape obtained by Kaiser Health News through a Kansas Open Records Act request.

“My Nevada crew is not available and my Parsons crew has declined,” the operator tells Fort Scott’s emergency line about a minute after taking the call. Then she says she will be “reaching out to” another crew. Nearly seven minutes passed before one was en route.

When Linda Findley sat at her kitchen counter in late May and listened to the 911 tape, she blinked hard: “I didn’t know that they could just refuse. … I don’t know what to say about that.” Both Mercy and Air Methods declined to comment on Findley’s case.

When Mercy Hospital Fort Scott closed at the end of 2018, hospital president Reta Baker had been “absolutely terrified” about the possibility of not having emergency care for a community where she had raised her children and grandchildren and served as chair of the local Chamber of Commerce. Now, just a week after the ER’s closure, her fears were being tested. Read the full article here.